Putsching with Style

Across the northern hemisphere, political elites fret about real or imagined putsches. Americans invoke January 6th with ritual solemnity, while Germans fear resurgent Reichsbürger conspiracies, and Turkey’s Erdoğan summons phantom plotters on cue.

Such tremors are new to these republics. In Latin America however, the coup is no democratic failure: it is a time-honoured method of political transition, governed less by force than by form.

Whether delivered by generals in epaulettes, insurgents in rags, or judges in robes, the performance is central, as the figure who topples a government must look like a prophesied saviour. Constitutions may be discarded, but the narrative has to remain untouched.

A Repeating Ritual with History

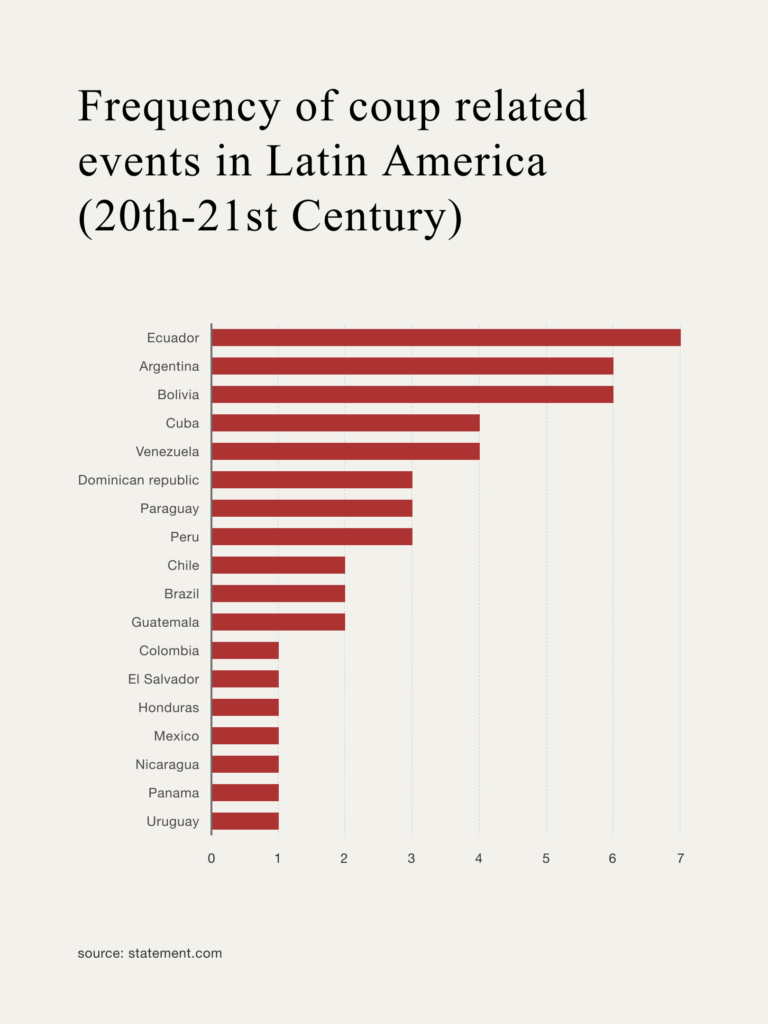

Between 1900 and 2020, Latin America experienced at least 97 successful or attempted coups, second only to Africa. This is not merely a statistical footnote; for the region’s history reads like a liturgical calendar of uprisings.

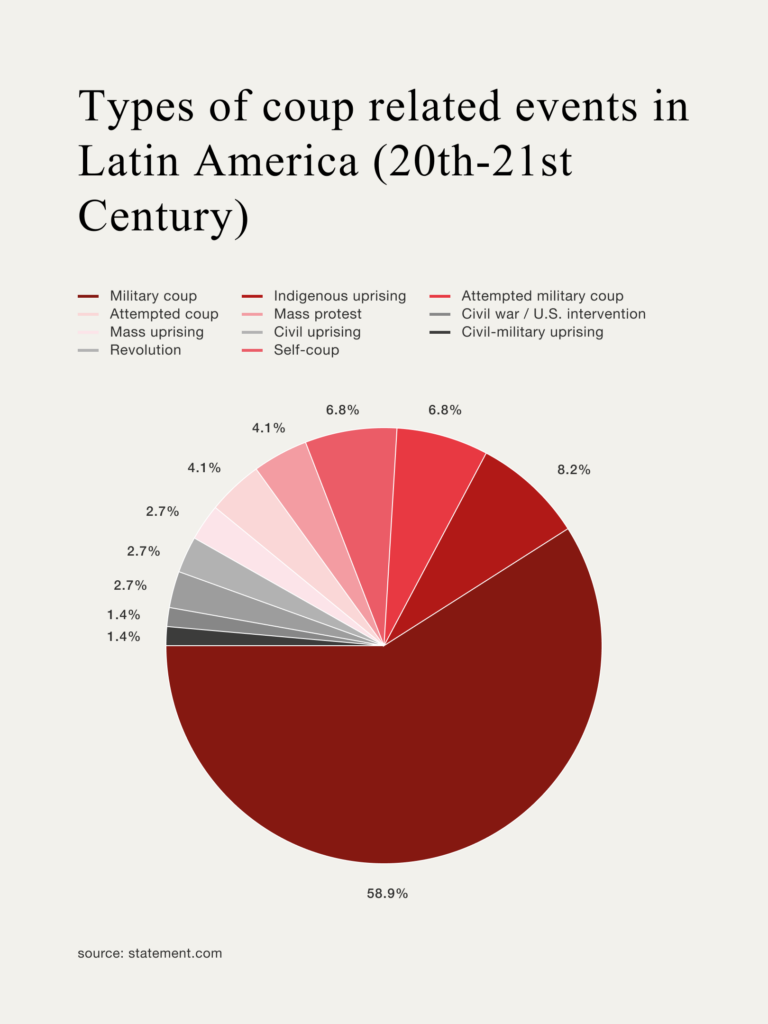

In Argentina, episodes from Uriburu in 1930 to Videla in 1976 followed a consistent script: troops marched in, the president vanished, and the junta proclaimed itself guardian of the nation. Brazil’s 1964 coup played out similarly. The military advanced, Congress applauded, and generals invoked family, order, and the nation with prayerful solemnity.

Chile in 1973 added drama to an already heady cocktail. Augusto Pinochet’s assault on La Moneda was filmed like a war epic. Salvador Allende’s suicide sealed the coup’s credentials as a great tragedy, and the cameras were there to record the establishment of a new order.

In Cuba, the coup came dressed as revolution. Fidel Castro entered Havana in 1959 as a mythical figure; when Batista fled, Castro’s subsequent conquest was presented as if it was a stage performance: Castro’s olive-drab fatigues, rifles held aloft, declarations from balconies.. This was not just the fall of another dictator: this was historical inevitability in action.

As military juntas fell out of fashion, the format evolved. Enter the autogolpe, the self-coup.

Alberto Fujimori in Peru dismissed Congress by fax and ruled by decree, claiming to have saved the nation. Jorge Serrano tried and failed to do the same in Guatemala, Rafael Correa in Ecuador used an apparent police uprising to gain power, and Fernando Lugo’s successful impeachment in Paraguay mimicked proper legality but was more akin to a legislative ambush. At last, Nayib Bukele in El Salvador sent soldiers into the legislature, not to seize it, but to posture.

These modern committers of coups wear suits, exercising power through legal fictions, carefully choreographed to maintain the illusion of order.

The Populist “Putsch”

Today’s strongman no longer needs to seize the palace. He merely has to suggest he might.

Brazil’s Bolsonaro floated hints of a coup like one would weather balloons. Morales in Bolivia was ousted under suspicion of electoral fraud, but returned through the mobilisation of his base. López Obrador campaigned as if a coup was imminent, even while in office.

The 21st-century coup is less about raw conquest and more about credibility. It does not need to actually happen; it only has to seem plausible enough to mobilise one’s base, while theatrical enough to leave an impression.

The Indigenous Counter-Ritual

Not all ruptures of the political order come from above: indigenous uprisings across Latin America offer a different take on the coup ritual.

These are not grabs for power, but rejections of the state’s legitimacy. Ecuador’s 1990, 2000, 2019, and 2022 protests paralysed the country with roadblocks, and the Zapatistas in 1994 used rifles, not to take over Mexico City, but to declare autonomy within the state of Chiapas.

Here, the coup is inverted, as its power lies not in the ability to seize state power, but to delegitimise it instead for not recognising the people’s complaints.

The Global Rehearsal

While the West debate the likelihood of a coup, Latin America’s myriad examples offer a brutal lesson: power and theatrics have merged there a long time ago. Latin America understands the putsch as a ritual—whether wrapped in populism, clad in legal formality, or driven by the forgotten people on the lower rungs of society.

The next coup may not begin with soldiers in the streets, but with a livestream, a press conference, or a vote of dubious legality. It might not succeed. But it will definitely be memorable.

Statement

In Latin America, coups have long since become rituals. The shifting of power there bears all the hallmarks of a carefully choreographed performance. From generals in uniforms to populists with cameras, legitimacy is taken, not given. While the West panics over imagined putsches, Latin America rehearses real ones with liturgical precision, a reminder that, in that region, power and theatrics go hand in hand.